I’ll begin this post with a parable:

Once upon a time, people developed software using the “waterfall” model. They would carefully write up a 30+ page specification for the product, and then they would spend a long time – several months to years! – developing the product to match the specification.

Then, of course, they would discover that the market had changed, or they had guessed wrong when they built the feature. And they would sigh, go back to work, and develop another 30+ page specification for the next release, which would come 6-18 months later and have the exact same problem.

And so the people suffered, until, about twenty years ago, someone realized that there was a better way to develop software. They said, “We’ve spent decades trying not to make mistakes in spec’ing out the product. But we always make mistakes, and because it takes us 18 months (and millions of dollars!) to know that we’ve made a mistake, our failures are painful and expensive! What if, instead of spending pointless hand-wringing hours trying not to make any mistakes, we devised a way to make the mistakes we inevitably make cheaper? What if we could find out about them faster, so that if we’re going to fail, we fail faster?”

And thus, the Agile development methodology was born. Instead of releasing monolithic software every 18 months based on an encyclopedia-size specification, software development teams produce working software in short development cycles (two weeks is considered optimal). At the end of the cycle, you demo your software to the customer, and get their feedback. Based on that feedback, you decide what to build in the next cycle.

The advantages of working this way are pretty obvious: you can only get so far off-track in two weeks, so mistakes are cheap, and because you are constantly getting feedback about your product, you can build something that will be much more useful to the customer/better suited to the market. Many if not most software teams are now using variants of this method.

So why am I talking about this in an artist’s blog?

Because, believe it or not, artists and software engineers have a lot in common. Both are doing creative work, both have an element of uncertainty in that work, and both need to be flexible about change in what they are building. Many Agile ideas apply in art as well, but the particular one I’m thinking of right now is this:

Fail faster!

At first blush, this seems silly. Why would you want to fail faster? We all want to succeed, don’t we?

But the truth is that mistakes are inevitable. What we want to avoid is expensive mistakes – ones we don’t find out about until the very end of the process, when it’s too late, or very expensive/labor-intensive to correct. We’ve all had projects that turned out to be disasters – like the mohair coat I spent months constructing, only to discover that the buttonholes weren’t placed correctly so the coat gapped open!

The point of “Fail Faster” is that we shouldn’t try to avoid making any mistakes. Instead, we should try to make our mistakes as inexpensive as possible – “Fail faster!” means identifying your mistakes – aka failures – faster, so they will be quicker and easier to fix. The point of the shorter development cycle is that it allows discovery and fixing of mistakes much more quickly than if you did the whole thing at once.

Now, how does this apply to the fiber arts? It’s all about the dreaded “S” word…sampling.

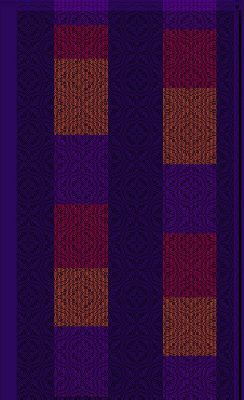

Sampling is important in a project precisely because it allows you to fail faster. As an example, consider the color simulation I did in Photoshop:

I didn’t like this design, and won’t be using it in my project. But notice that, by sampling it via Photoshop, I only took about 10 minutes to discover I didn’t like it. This mistake was far less costly than if I’d sat down and woven a physical sample, or, worse, woven up an entire piece! I “failed faster” using this simulation/sample, and it saved me a lot of time and grief.

Sampling is a way of reducing risk. Instead of developing a monolithic project to a set of untried specifications – basically, using the waterfall method and gambling everything on a single throw of the dice – sampling allows you to develop things iteratively, trying out new ideas and fixing mistakes in short development cycles. The bigger the project and the more uncertainty around it, the more value there is to sampling. It’s as simple as that.

You’ve stated my attitude toward sampling in a way that didn’t occur to me before. Hopefully people will see the value of sampling in a different light. Thanks!

Ditto what Laura says. As for using the computer to fail faster………….there is the very real possibility that what looks awful on the computer screen would look absolutely ravishing in the right yarn. I would think it better for a weaver to see how she/he might be able to sample faster. Perhaps at first really narrow warps just to get a feel for the possibilities, then a wider warp to work on the narrow samples that you liked, and then a still wider warp to work out difficulties? Perhaps you can think of many more ways to make the sampling–and hence the failing–go faster?