The last two years have been a bit of a puzzle for me. I’ve done virtually no weaving – which is pretty darn odd, considering I quit my job so I could focus on developing my career as a textile artist. At first I thought it was because I was busy doing other things – mostly, working on my business and fulfilling my duties as Board President at the San Jose Museum of Quilts and Textiles. Both of those took (and are still taking) a ton of time and emotional energy. But two years? I was starting to wonder if I’d made a mistake buying a jacquard loom, because I seemed to have very little interest in weaving. But I couldn’t seem to come up with anything that triggered my enthusiasm.

Then two things happened. The first was getting a close look at Itchiku Kubota’s kimono, which are both beautiful and masterful. Conceiving and executing these kimono requires not only vision, but impressive technical skills and deep understanding of the design possibilities of each technique. Years of technical mastery are needed to make them.

This is very different from how most textile artists currently work. Current textile art emphasizes message; it’s about what you’re saying with your art, not about the skill and precision with which the art is made. In fact, too-good construction can even make your work suspect, because good craftsmanship is associated with craft, not art. (Insert the usual arguments about craft vs. art here.)

As a result, most of the textile art I’ve seen recently, while powerful, has been pretty simple, technically speaking. Most of it could be composed by someone with just a few years of experience, and made within a matter of weeks or months. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with that style; it’s a perfectly valid approach to art, and it results in some remarkable pieces. It works for a lot of artists.

But it doesn’t work for me. My natural preference is for work that is intricate; that combines multiple media; that requires technical mastery; and that takes many months or years to complete. But I’ve seen relatively little modern work that fits that description. (Except for the American Tapestry Alliance shows, which I love!)

So when I asked a lot of established artists how to study and develop a career as a textile artist, much of their advice on who and what to study came from a body and philosophy of art totally different from what I loved. And I didn’t see my style of work reflected in any of the textile art I’d seen. Technical virtuosity seemed stuck in a past that emphasized skill over creativity; modern art emphasized creativity and downplayed skill. Who was doing the kind of complex, technical art that I wanted to do? Where was my tribe?

Alice Walker, in her essay “Saving the Life that is Your Own: The Importance of Models in the Artist’s Life,” says:

In that story I gathered up the historical and psychological threads of the life my ancestors lived, and in the writing of it I felt joy and strength and my own continuity. I had that wonderful feeling writers get sometimes, not very often, of being with a great many people, ancient spirits, all very happy to see me consulting and acknowledging them, and eager to let me know, through the joy of their presence, that, indeed, I am not alone.

Kubota made my kind of art. Seeing his kimono sent a shock of recognition through me. This is the kind of work I want to do…that intricacy, that breadth of vision, that fusion of multiple disciplines. Yes, yes, a thousand times yes! And – having finally found my tribe – I suddenly felt less alone, and a lot more hopeful.

Another thing that has really encouraged me was a discussion I had recently with a museum curator. We were talking about another jacquard artist’s work, and the person I was talking to said, “You know, I think she did herself a disservice when she decided to limit herself to what could be done on a jacquard loom, as opposed to using whatever technique would help her say what she wanted to say.”

I stopped for a moment, thunderstruck. Oh! Duh!

Because, of course, I had fallen into the same trap. It’s a natural mistake: when you buy a very expensive hammer, it’s hard not to feel that you need to pound a LOT of nails to justify your purchase. So, having bought a jacquard loom, I had naturally been envisioning myself as a jacquard weaver – weaving exquisite pieces that exploited the powerful capabilities of the loom. And focusing on weaving to the exclusion of other disciplines.

But I’ve never been terribly excited about handwoven cloth. (Yes, I know that’s a strange confession for a well-known weaver.) To me, cloth is mainly interesting as a raw material for other processes – dyeing and sewing, maybe origami. And flat cloth? It leaves me, well, flat. Since I had been envisioning jacquard-woven flat wall hangings, is it any surprise that I lost my enthusiasm for starting new work?

The last revelation I’ve had has to do with the question of art vs. artistic career. My style of art is quite different from most of what is currently being exhibited and sold. And because I want to put hundreds or thousands of hours into each piece, building a body of work will be really slow. As a result, taking my approach may seriously impact my career as an artist. I have been noodling unhappily over this for the last two years. Kubota’s kimono have knocked me clean off the fence I was sitting on, because if I can make work like those kimono – or even get close – I do not give a flying fuck about whether I ever have an artistic career.

Which, I think, finally qualifies me to call myself an artist. 🙂

There’s a wonderful passage in Richard Bach’s Illusions that describes how I feel. The protagonist (Richard) has been barnstorming around the Midwest, offering people short airplane rides for a small fee. In the process, he meets the Messiah, whose name is Donald Shimoda. Richard decides he wants to be a Messiah too, so he studies with Donald. In this section, Richard has just given his “Sermon on the Mount” teaching to Donald for the umpteenth time:

I looked at him. “Too wordy?”

“As always. Richard, you are going to lose ninety percent of your audience unless you learn to keep it short!”

“Well, what’s wrong with losing ninety percent of my audience?” I shot back at him. “What’s wrong with losing ALL my audience? I know what I know and I talk what I talk! And if that’s wrong then that’s just too bad. The airplane rides are three dollars, cash!”

“You know what?” Shimoda stood up, brushing the hay off his blue jeans.

“What?” I said petulantly.

“You just graduated. How does it feel to be a Master?”

“Frustrating as hell.”

He looked at me with an infinitesimal smile. “You get used to it,” he said.

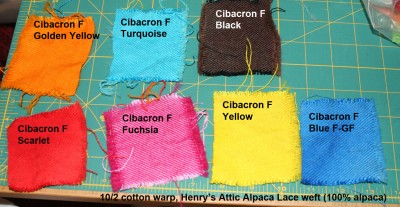

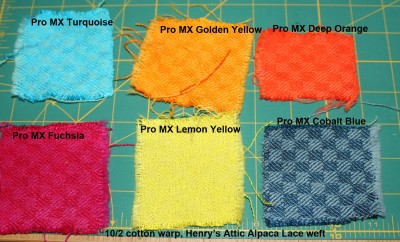

Having thought through all that, I have some very exciting ideas for combining jacquard designs with dyeing. In particular, I want to cross-dye jacquard-woven cloth woven from cotton and polyester threads. Cotton and polyester are ideal for this purpose because dyes for cotton (fiber-reactive dyes) do not dye polyester, and dyes for polyester (disperse dyes) do not dye cotton. So you can weave a pattern in white on white, print on the fabric using fiber-reactive dyes, and then dye it in a different design using disperse dyes. The finished piece will show the cotton in the fiber-reactive pattern and the polyester in the disperse-dye pattern.

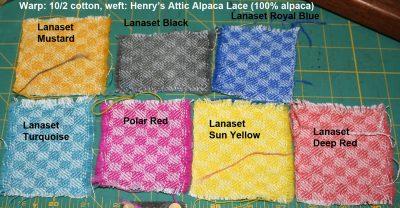

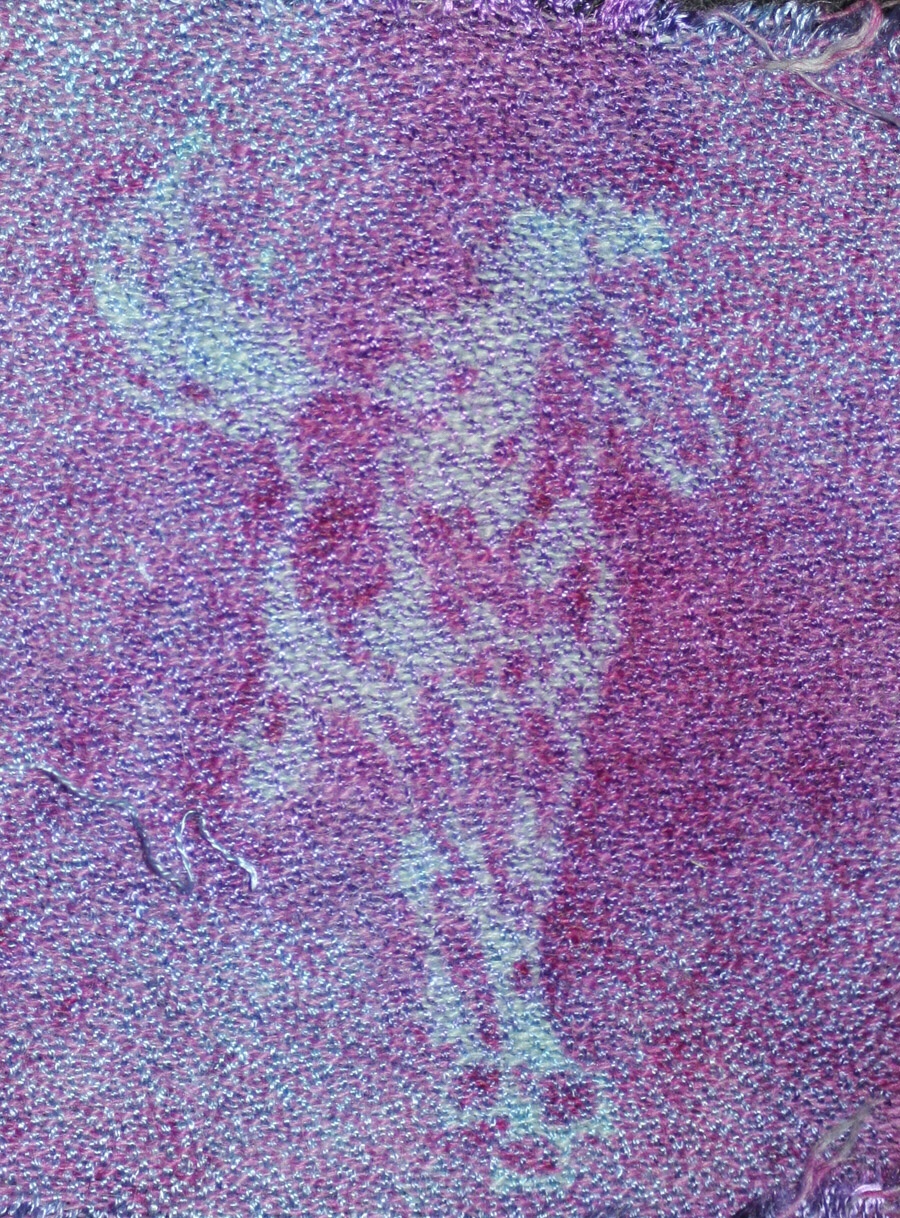

This is a bit hard to envision, so here is a sample I made a few years ago while playing with this idea. The warp is Tencel (or maybe cotton), the weft is alpaca, and it’s dyed with both acid and fiber-reactive dyes. The pale blue fiber-reactive dye is applied first (it dyes both cotton and protein fiber), then the thickened red-purple acid dye is stenciled on. The acid dye dyes the alpaca but not the silk, giving an interesting pebbled texture. (You can read more about the process in this blog post.)

This is pretty interesting in itself, but throw in a jacquard loom and some really interesting stuff becomes possible. For example: suppose you weave an image of a tree, where the tree is woven in polyester and the background in cotton or mostly-cotton. You can weave the trunk of the tree in a “bark” pattern that is mostly polyester with some textured cotton ridges going through it, and then paint different colors/designs on the polyester and the cotton parts of the bark. You could weave birds in cotton half-hidden against a canopy of polyester leaves. Then you could stencil a pattern of light and dark green on the polyester leaves without touching the birds, and come back and paint the cotton birds later.

Or you could go abstract and do shibori or tied-resist dyeing (twice!). Or you could try to do woven shibori! Depending on thickness, polyester thread may be strong enough to use as tie threads…and polyester has memory, so there is also the option of permanently-set crimp cloth. The possibilities are truly endless, and well worth exploring. This could be a LOT of fun!